Describe two to three classroom situations (e.g. rising hand to speak for example) that you would encounter in an early childhood classroom.

After reading Chapter 9,

Save your time - order a paper!

Get your paper written from scratch within the tight deadline. Our service is a reliable solution to all your troubles. Place an order on any task and we will take care of it. You won’t have to worry about the quality and deadlines

Order Paper Now Social and Emotional Development

and the Social Studies

CHAPYER 9 BELOW

© Radius / SuperStock

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

- Describe the kind of environment and teacher interaction patterns that support early learning standards for social and emotional development.

- Explain how teachers can help children acquire identity and self-esteem and develop socialization skills.

- Describe the importance of

self-regulation and how teachers help children develop self-control and learn

to solve problems and conflicts. - Identify important concepts in the national

standards for the social studies and resources, activities, and themes

appropriate for young children.

Introduction

From the Field

Director Lucia Garay explains the difficulties related to identifying and describing emotionally healthy children.

Critical Thinking Question

- Lucia explains how important it is to address social/emotional considerations as part of an integrated approach to teaching. Why is this so important?

You know that in addition to meeting children’s physical needs and approaches to learning standards, a very important part of teaching young children is promoting and encouraging healthy social and emotional development. Some of the families of your class group are experiencing great stress—at least one family in your class is struggling with unemployment and at risk of losing its home, another has a military parent deployed to a combat zone, and a third is providing in-home care for a grandparent who recently had a stroke. You wonder how these circumstances might affect the children’s emotional stability and behavior and how you can help all the children to become confident in their ability to deal with challenges and solve problems they experience at school.

You want the children to develop a strong sense of self and relate well to their teachers and peers. You also want to incorporate a developmentally appropriate approach to encourage them to regulate their own behavior and create a caring and vibrant classroom community. In this chapter, we explore important concepts and effective strategies for social and emotional development and a developmentally appropriate approach to social studies curriculum and standards.

9.1 Early Learning Standards for Social and Emotional Development

As described in Chapter 4, the social and emotional needs of young children vary by age, personality, and circumstances. Social psychologists, led by Erik Erikson (1950), consider it critically important that young children develop secure attachments and trusting relationships, a positive self-image and confidence, independence regulated by awareness of and sensitivity to others’ feelings and expectations, and the ability to make and keep friends and function as a member of a community. These ideas provide the framework for early learning standards that focus on social and emotional development and are consistent with the 1997 National Education Goals Panel recommendations. Social and emotional development is an important element of early childhood curriculum for a number of reasons related to the development of resilience, self-regulation, and early childhood as a window of opportunity.

Resilience

Children who acquire the skills emphasized in the early learning standards for social-emotional development are far more likely to be resilient, able to cope with stress and overcome adversity.

(McClelland, Cameron, Wanless, & Murray, 2007; Pawlina & Stanford, 2011; Pizzolongo & Hunter, 2011). The kinds of significant challenges children face today include violence, abuse or neglect, natural disasters, economic distress within their families, and separation from loved ones. They also experience the typical developmental dilemmas that emerge as they begin to form friendships, experience rejection, and bond with unfamiliar adults.

Resilient children display a sense of agency, a feeling of control over their own decisions, and confidence in their ability to solve problems. They also do better in school over the long term. Their mindset tends towards optimism in face of a dilemma or challenge (Pawlina & Stanford, 2011, p. 31). People without resilience, in contrast, feel powerless to improve their circumstances or solve problems (Pizzolongo & Hunter, 2011).

Consider the family caring for a disabled grandparent and the range of reactions the child might display—the resilient child might see his grandpa’s illness as an opportunity to spend more time with him, reading books, sitting with him in the room and helping his parents with care needs; the child with a lack of resilience might instead pick up on a sense of parental distress, feel anxious, and act out for attention as he observes his parents spending time caring for grandpa when he feels he needs their attention himself. Children with special needs face additional challenges and may particularly need to develop skills associated with resiliency (McClelland, Cameron, Wanless, & Murray, 2007).

Self-Regulation

Self-regulation is the ability to make decisions to control impulses in varying situations. An increasing body of research confirms strong links between early and long-term academic success and a child’s ability to regulate her own behavior, work independently, control impulses, and follow directions (McClelland, Cameron, Wanless, & Murray, 2007; Papalia & Feldman, 2011). These are learning skills that emerge with the development of executive functioning, as stressed in the Approaches to Learning standards (Chapter 7). While multiple factors including temperament, brain development, and home environment contribute to shaping these abilities, teachers certainly play an important role in helping children learn how to thrive in educational environments (Jewkes & Morrison, 2007).

Social and academic competence is linked to classrooms with warm and responsive teachers and positive teacher-child interactions. Self-regulation that is internally motivated, rather than a response to expected rewards, also seems to develop best in classrooms where children have many opportunities to make and be accountable for their own decisions (Pianta, LaParo, Payne, Cox, & Bradley, 2002).

The Early Childhood Window

© iStockphoto / Thinkstock

A secure relationship with important adults sets the stage for healthy social and emotional development.

Brain research points to the importance of acquiring these learning-related skills during the early childhood period (Masten & Gewirtz, 2006). The field of early childhood education has long emphasized the need for social and emotional competence and teachers who understand how children construct their social selves in a similar hands-on fashion as in other areas of development; studies today confirm more than ever that this continues to be the case (Saracho & Spodek, 2007).

In the next two sections, we explore a social environment that promotes healthy development of these qualities and how teachers facilitate development of self-concept, social competence, and self-regulation.

The Social-Emotional Learning Environment

Providing an environment that promotes healthy social and emotional development requires considering the social ecology of the classroom (van Hoorn, Nourot, Scales, & Alward, 2011), or how interaction patterns vary according to setting and type of activity. Think of social ecology from the perspective of Bronfenbrenner, as a network of individual personalities as well as overlapping peer groups, characterized by different ways children join, create, or are assigned by others—by popularity, interest, friendship, ability, and so on. Understanding group identification as a natural human activity is important, since groups can have an impact on the social development of individuals (Kindermann & Gest, 2009).

For instance, a teacher creates an artificial social ecology by assigning children to permanent or fixed reading groups using a single characteristic such as ability (homogeneous grouping). Subsequently, the children may recognize these distinctions and label their peers in these groups as “smart” or “dumb” and behave toward one another with this label in mind. Classroom ecology evolves more naturally when teachers vary the assignment of children to working groups (heterogeneous grouping) and monitor how children create and self-select their own membership in groups. Teachers learn a great deal about individual strengths and needs from observing the ways children form groups and interact with one another.

In the class discussed above, those same children whom the teacher labeled by ability might categorize themselves by interest, such as “artists,” or “block builders.” Or they might develop perceptions about ability but express them differently, such as “fast runners” or “good storytellers.” Of course it is also possible that some group assignments would not be positive, such as “troublemakers” or “mean kids.” Teachers use this information to help individual children with social skills and to guide groups toward inclusive and positive interactions.

Social acceptance, rejection, confidence levels, and self-image are all affected by social ecology and can also be very distinctive, fluid, or idiosyncratic from one class to the next. Teachers are most likely to establish a positive social atmosphere when they:

- Help children separate from parents and integrate quickly into the flow of classroom activity (Hendrick & Weissman, 2007; van Hoorn, Nourot, Scales, & Alward, 2007), so that they don’t remain isolated or begin the day as bystanders.

- Build an inclusive, responsive, and diverse community (van Hoorn, Nourot, Scales & Alward, 2007) that values similarities and differences.

- Establish a positive verbal environment (Meese & Soderman, 2010) that sets the stage for friendly social interactions.

- Create opportunities for developmental levels and types of play that promote face-to-face contact and socialization (Fox & Lentini, 2006; Howes & Lee, 2007; van Hoorn, Nourot, Scales & Alward, 2007).

- Intentionally teach and model appropriate social skills (Fox & Lentini, 2006; Howes & Lee, 2007).

Helping each child feel comfortable and safe at school or care is best achieved with a gradual approach. Preenrollment visits and individual interactions with the teacher build trust. Small-group play before whole-group activities helps children get to know each other. Acknowledging, modeling, and helping children express their feelings from the start allows them to feel emotionally safe and secure (Hendrick & Weissman, 2007).

© Corbis / SuperStock

Teachers understand that part of establishing

a positive social climate is helping families establish separation routines that allow the child to transition easily into school or care.

Building community is an ongoing process that also starts before children enter the program, with home visits as well as written and verbal communications. It continues every day as teachers welcome children, establish routines that involve them in caring for the classroom and each other, and plan and conduct activities that help them learn about the concept of community and investigate the community in which they live and go to school or care.

Teachers establish a positive verbal environment when they use language to demonstrate respect for children and their abilities by showing genuine interest in their activities and asking a variety of questions. Perhaps a teacher might say, “Wow, I see that you have brought in some very interesting rocks to share with us—can you tell us about where you found them and what you know about them?” Teachers model courtesy and help children understand expectations with language such as, “It would be so helpful if you could . . . ” Or “Thank you so much for putting your trucks away—you knew right where they belong.”

Teachers should also encourage children to use their words to describe the choices they make, with opportunities to make decisions that are meaningful and important (Meese & Soderman, 2010). For example, a teacher might say, “I see you have put the ‘work in progress’ sign on your block structure—you must have some big ideas about what you are building—can you tell me about what you want to do next?” These kinds of verbal interactions help children feel valued and special and create conditions that affirm positive perceptions of themselves and others.

The positive verbal environment can be used as a context for facilitating play interactions as teachers establish defined activity areas and pathways to allow for different types of social exchange. For example, by choosing and arranging furniture and equipment that encourage face-to-face encounters, teachers increase the chance that children will engage with one another (van Hoorn, Nourot, Scales, & Alward, 2007). A comfortable area with pillows or soft furniture and homelike lighting for reading and looking at books encourages conversation and personal interactions. A playhouse in the outdoor space invites children to congregate and play in small groups.

Direct teaching and modeling takes many forms, from having a conversation with an individual child about how to communicate anger with words to guiding three children through settling a dispute or constructing a set of “friendship guidelines” with an entire group or class.

Teacher Practices and Interaction Patterns

© iStockphoto / Thinkstock

Teachers use words and body language to show affection for and interest in individual children.

In many ways, a teacher or caregiver’s behavior and interaction patterns are as important to children’s social and emotional development as any materials or activities in the classroom (Copple & Bredekamp, 2009; Gallagher & Mayer, 2006; Willis & Schiller, 2011). In general, regardless of the age of children, teachers support social and emotional or affective development by building high-quality relationships with them. The specific characteristics of teacher-child interactions will vary over time and by age as teachers get to know their children, become familiar with them as individuals, establish mutual trust and respect, and commit to a long-term relationship with each child and family (Gallagher & Mayer, 2006).

Teacher behaviors that promote high-quality relationships

include:

- Using words and body language that show affection and interest for individual children

- Responding promptly to children in distress

- Engaging in personal interaction or conversation with each child daily

- Recognizing and acknowledging individual and group accomplishments

- Respecting children’s need or desire for privacy

- Respecting children’s need or desire to finish an activity

- Providing children with a number of choices or directions that are manageable for their age

- Waiting to see if children can solve a problem independently before intervening

- Using positive language (I need you to . . . can you please . . . ) to convey expectations (rather than ‘no, don’t’, etc.) (Gestwicki, 2011)

9.2 Self-Concept and Socialization

Self-concept begins to develop very early, as babies first realize that their limbs are part of their bodies; it grows as toddlers, for example, begin to recognize their images in a mirror (Papalia & Feldman, 2011). This is a multidimensional concept that also affects how a child develops relationships with others.

Children acquire personal identity as they learn to recognize and feel comfortable with their self-images and bodies. They begin to understand their social identity as comprising the kinds of things that characterize them as individuals within larger groups, such as ethnicity, culture, gender, and social standing (Derman-Sparks & Edwards, 2010; Kowalski, 2007). They develop an attitude of confidence and an internalized sense of self-worth as they experience repeated success at completing tasks and solving problems. Young children also begin to develop empathy—the ability to imagine or understand how another person might feel in different situations. All these things are needed for a child to build healthy social relationships with peers and others.

Personal Identity

Young children tend to describe themselves in concrete terms, according to what they look like, what they can do, or what they like or don’t like. They can’t typically provide a description with multiple, integrated or qualitative characteristics until middle childhood (Hendrick & Weissman, 2007). Therefore it makes sense to do activities with them that focus on these concrete attributes so they can begin to develop a vocabulary for describing themselves in terms of things that are real to them, such as, “I have brown eyes” or “I like to dance.” Table 9.1 offers suggestions for steps teachers can take to foster a sense of self.

| Table 9.1: Strategies for Promoting the Development of Personal Identity | |

|---|---|

| Activity Focus | Sample Activities |

| Mirrors |

|

| Photographs |

|

| Names |

|

| Accomplishments |

|

| Preferences |

|

Social Identity

Acquiring social identity includes learning about gender, ethnicity, and ability issues. Experts on multicultural and antibias education advise teachers to focus on values, interaction patterns, and equitable teaching practices, rather than curriculum activities that highlight superficial features like flags or potentially stereotypical images of different cultures, such as a sombrero or feathered headdress (Derman-Sparks & Edwards, 2010; Hendrick & Weissman, 2007). In other words, children are taught to respond to each other courteously as individuals. This helps to create a classroom culture that values respect, caring, and the matter-of-fact recognition of similarities and differences. It also provides the grounding children need as concrete learners to understand their places in the context of others.

Strategies that promote an accurate and unbiased environment include the following:

- Using pictures of actual children and families rather than drawings.

- Making sure that photographs, displays, and materials depict at a minimum the ethnic groups represented in your class; also be sure that people of all ages are represented.

- Examining and removing any literature that includes stereotyping of any kind.

- Using only materials that are culturally inclusive and gender-neutral (e.g., showing both men and women in different occupations).

- Encouraging children to bring materials from home for the dramatic play area.

- Making sure that dolls in the dramatic play area accurately reflect ethnic features rather than dolls that are identical except for skin pigment.

- If you notice “gendrification” in play areas, where, for example, only girls are playing in the kitchen area, designate “girl only” or “boy only” days in those centers to encourage cross-gender participation.

- Making sure classroom job assignments are gender-neutral.

Activities that can be used in the classroom to contribute to development of social identity include the following:

© iStockphoto / Thinkstock

As children acquire a concept of their social self, it is important to support gender-neutral play that doesn’t steer children into stereotyped roles.

- Cut out and paint a life-size tracing of each child’s body and display these in small groupings, or as a “class portrait.”

- Mix paint to match the skin color of each child when making portraits, or to do handprints or footprints.

- Have children cut out pictures from magazines to make a book or collage of boys and girls doing similar things.

- Make personal time lines with photographs children bring from home that depict important events in their lives.

- Make class books of things children like or don’t like to eat or do, or things they fear or that make them happy or angry.

- Pair or group children to ensure cross-cultural and balanced gender interactions.

Confidence and Self-Esteem

As children’s cognitive awareness and ability to use words to describe “who I am” develops, they also begin to make comparative judgments about themselves in relation to others. Children tend to have perceptions about their self-worth long before they begin to talk about it, which typically occurs toward the end of the early childhood period (around age 7 or 8) (Papalia & Feldman, 2011). Younger children also seldom make subtle distinctions, usually categorizing themselves at one or the other end of a spectrum, such as good/bad. Further, their ability to be realistic about strengths and weaknesses can be affected by adults who lavish unwarranted praise or who are continually critical.

Essential to healthy self-esteem and confidence that motivates children to persist through difficulties is “unconditionality” (Papalia & Feldman, 2011). In other words, if a child’s self-esteem is solely contingent on success, she can develop a sense of helplessness if she is not successful on the first try. Conversely, if a child’s self-esteem and confidence are unconditional attributes, a failed attempt will only lead him to try repeatedly until he succeeds. Over time, children who lack confidence expect to fail and become more reluctant to take risks, while an overconfident child may not learn how to react to failure (Willis & Schiller, 2011).

The goal for teachers of young children is to help them develop realistic confidence in several ways, as Table 9.2 illustrates.

| Table 9.2: Strategies and Examples for Developing Confidence and Self-Esteem | |

|---|---|

| Strategy | Example |

| Encourage trial and error, so children learn that mistakes are a normal part of progress and the way we learn what does work. | Trying several different combinations of paint to make green. |

| Share your own experiences with success, failure, and problem solving. | “Last weekend I was making cookies and I burned them all in the oven; I had to start over, but the second time, I set a timer, and that batch turned out great!” |

| Identify challenges. | “Wow, our plan for the garden is going to include a lot of digging and hard work, but I know if we take our time and work together, we can do it!” |

| Model talking through options or pros and cons for solving a problem so that children see that decision making is a process. | “Well, if you want to put a tower on top of this airport, there are a couple places it could go. Let’s think about what might happen if we put it here or there before we move the blocks.” |

| Read stories to children that provide good examples of how one finds success and deals with failures. | See the appendix for a list of children’s books geared to social-emotional development. |

| Emphasize the value of trying something new as an important part of learning. | “This puzzle doesn’t have the little knobs you are used to, but look at the great dinosaur picture on the cover of the box—it shows what it will look like when the puzzle has been put together.” |

| Acknowledge accomplishments. | Documenting with photos, displaying work, sharing a construction or art product during group time with other children, etc. |

| Praise effort over ability. | “I know you tried three times to cut that paper circle to get it just right.” |

| Sources: Gartrell, 2012; Pawlina & Stanford, 2011; Willis & Schiller, 2011. | |

Empathy

As defined earlier, empathy is an abstract concept that develops over a long time. Very young children generally do not experience or express empathy. Infants, toddlers, and young preschoolers tend to be highly egocentric, acknowledging only their own needs and assuming that everyone experiences the world from a single perspective—theirs (Piaget & Inhelder, 1969)! It would not be effective, for example, to address an 18-month-old child who bit another child with, “That was mean! How do you think you made him feel?”

The teacher or caregiver could, however use such an episode as an opportunity to begin building empathy. The teacher might say, “Oh, you hurt your friend,” and ask the biter to help comfort the other child, perhaps by holding his hand or helping to hold ice on the bite. Parents, teachers, and caregivers can encourage children—beginning around age 3—to consider how others are feeling, keeping in mind that it takes many such experiences for empathy and compassion to grow.

As with many other dimensions of social learning, it is essential to use language to help children recognize what others are feeling or thinking. You might, for example, say “Remember this morning when you couldn’t find the block you were looking for and you got upset? I see that Molly is getting frustrated because she can’t find what she is looking for—can you help her?” Here you are letting both children know that emotions and feelings are universal and that one can demonstrate sympathy and concern.

Caregivers can support the development of empathy by providing children with opportunities to care for and recognize emotional signals and body language in others. Children should also be encouraged to consider the fact that different people have different perspectives about the same situation. Simple activities such as looking at, describing, or drawing an interesting seashell from multiple angles, or asking children what they see when they lie on their backs and look up at the sky, provide concrete reference points for discussing point of view.

Additional caretaking activities that help children to develop empathy include:

© Fotosearch / SuperStock

Adults model compassion and concern,

which helps children learn to respond to others in distress.

- Encouraging children to wash, dress, feed, change, and speak to baby dolls in the dramatic play area.

- Caring for classroom pets—even a fish needs daily care; provide a feeding schedule and record children’s daily observations about what the fish is doing or how it is behaving. If your state allows other kinds of pets, consider inviting children to take a pet home over a weekend.

- Noting when a child is out sick and making cards or sending a note/email message to a child at home.

- Using sticky notes to jot down brief anecdotes when you observe a child doing something thoughtful or particularly sensitive to another child’s feelings; put the sticky note in the child’s take-home materials or make a wall chart.

To help children learn to recognize and acknowledge others’ feelings, try activities such as:

- Making “persona dolls” (Derman-Sparks & Edwards, 2010)—simple rag dolls that children name and for which you make up a back story relevant to the circumstances of children in your group. Use them to role play empathetic interactions.

- Making stick puppets, each with a photo/face of a child in the classroom. Use them to reenact caring or hurtful interactions that you observe.

- Giving plush animal puppets names like Fearful Frog, Sickly Snake, Angry Alligator—thus encouraging children to use them for role playing.

- Making or buying a matching lotto-type game that incorporates facial expressions indicating feelings—delight, anger, frustration, boredom.

- Making a book with pages that start with, “I feel sad when. . . . I feel happy when . . . .” Record children’s responses and keep your record handy to read frequently.

- Singing songs like “If you’re happy and you know it, clap your hands . . . if you’re angry and you know it, stomp your feet. . . .”

Healthy Social Relationships

More From the Field

Director Beverly Prange offers examples of the range of social behaviors a preschool teacher might expect.

Critical Thinking Question

- How did Beverly’s comments relate to considerations for planning the physical environment to support social interactions?

With young children, developing healthy social relationships depends a great deal on a general feeling of safety and confidence (Willis & Schiller, 2011) as well as on established interactions with family members and caretakers, and making/maintaining friendships in the neighborhood and at school or child care (Howes & Lee, 2007). One of the most heartbreaking things a teacher can witness is a child who is a social outcast, unable or unwilling to make friends, clearly miserable and unhappy most of the time. Infants as young as 2 months begin to distinguish peers from others and by 2 years of age have begun to display preferences in play partners (Kowalski, 2007; Ladd, Herald, & Andrews, 2006).

Play-based group settings that provide children with adequate space, time to play, open-ended and creative activities support positive and complex interactions between and among children more than those with highly directed programs and limited access to materials (Howes & Lee, 2007; Ladd, Herald, & Andrews, 2006). Important as well is evidence that close and trusting relationships between children and their teachers provide children with emotional resources that help them manage stress and aggressive tendencies (Gallagher & Mayer, 2006; Gallagher, Dadisman, Farmer, Huss, & Hutchins, 2007; Howes & Lee, 2007; Ladd & Burgess, 2001). Two challenges for teachers to help children develop healthy social relationships are promoting peer-group acceptance and facilitating and creating the conditions for children to form friendships with other individuals.

Peer Acceptance

© Visions of America / SuperStock

Children who want to join play stand a better chance of being welcomed if there are four or more children already in the group.

Through observation and interactions with children, early educators learn to distinguish between general acceptance of a child by his peers and true friendships between individual children characterized by mutual affection, companionship, and longevity (Kostelnik, Soderman, & Whiren, 2007). The factors that attract children to their peers are very similar to those that attract adults—shared interests, personality, appearance, and behavior (Howes & Lee, 2007; Kowalski, 2007).

General peer acceptance is important, since much of a child’s day at school or care involves interactions with others in play, small- or large-group activities with adults, snacks and mealtimes, story time, or rest. Some of these activities are more “high profile” than others; for example, if a child states loudly, “Ewww, I don’t want Timmy to sit with me at lunch,” it is likely other children will hear and the probability of Timmy being rejected by others increases (Ladd, Herald, & Andrews, 2006). Further, once a child has established a negative reputation, that reputation becomes more and more difficult to overcome, and it becomes harder for the child to form individual friendships as well (Buhs & Ladd, 2001; Gallagher et al., 2007; Persson, 2005).

Because play is typically a fluid activity, with children moving about and highly engaged in what they are doing, a child can “practice” negotiating relationships with peers by inviting others to play or asking them to join a play in progress. Studies have shown that children are most successful in their attempts to join group play when teachers encourage them to:

- Approach a group of four or more children, as the personal dynamics of pairs and triads are characteristically more exclusive and likely to result in a rejected offer or request.

- Observe for a few minutes so the child can gain a sense of what is going on, and then make an effort to join the play by imitating what other children are doing and using language that focuses on the group, rather than on themselves. For example, instead of saying, “I want to play,” a child will be more successful by asking, “Can I help you build the bridge?” (Ladd, Herald, & Andrews, 2006.)

Teaching Friendship Skills

Young children communicate and cooperate more with their friends than with other children (Howes & Lee, 2007; Kowalski, 2007). They also have more conflicts but usually find ways to resolve them (Kostelnik, Soderman, & Whiren, 2007). Over time, from spending a lot of time together and sharing experiences (mutual socialization), they may even take on similar characteristics or preferences, such as hairstyles, clothing, or musical tastes (Howes & Lee, 2007; Kids Matter, 2009).

Young children are more likely to make friends when they are able to use their words effectively to initiate conversations, express feelings, provide ideas for play, and compliment other children. They are also more successful when their behavior is generally helpful and cooperative, demonstrating the ability to share and take turns, refusing to join in others’ negative behavior, playing fair, following rules, and being good losers (Bovey & Strain, 2012; Kids Matter, 2009).

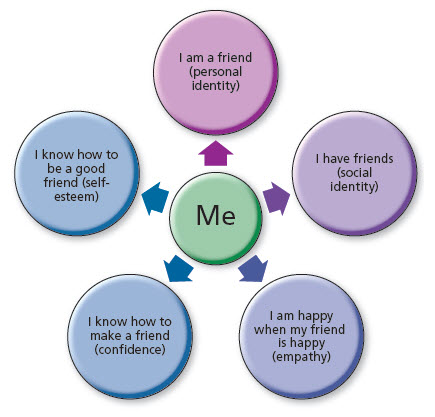

Engaging young children with activities that model and teach friendship integrates all the elements of self-concept, as Figure 9.1 shows.

Figure 9.1: Friendship as an integration of the elements of self-concept.

Engaging young children with activities that model and teach friendship integrates all the elements of self-concept.

Many types of activities can be used to promote friendship, pro-social skills, and a sense of community and belonging. Such activities might include those listed in Table 9.3.

9.3 Promoting Self-Regulation

Self-regulation links all the domains of development and is considered one of the most reliable predictors of academic and social success in later life (McClelland, Cameron, Wanless, & Murray, 2007; Papalia & Feldman, 2011). It is important during early childhood because children need to learn how to delay gratification; respond and adapt to rules; and handle frustration, challenges, and disappointments in socially acceptable ways. We want them to do so not only because of the sense of satisfaction they feel when they know they are making good decisions but also because being able to control themselves sets them up as more likely to achieve success as adults.

Adults promote self-regulation when, before stepping in to help, they wait to see if the child can solve a dilemma alone. That is, they wait not so long that the child becomes frustrated and angry or at risk for getting hurt but to communicate confidence that at some point they expect that the child will be able to solve problems independently.

Behavior Management

The primary goal of classroom or group-care behavior management is not for the teacher or adult to manage the children but for the children to learn how to regulate themselves. Behavior is the visible representation of the child’s effort at any given moment to integrate what he or she wants or feels with what he or she chooses to do.

Many factors motivate children’s behavior and the decisions they make, and a “one size fits all” approach to classroom management is neither universally effective nor considered developmentally appropriate (Copple & Bredekamp, 2009; Kohn, 1999). A sound approach to guidance includes the following:

- Building a trusting relationship with each child

- Accepting feelings children express without judgment

- Determining the precipitants or causes of behaviors

- Establishing guidelines that allow for a range of consequences rather than a fixed or predetermined punishment

- Intentionally teaching and modeling decision making

- Regarding children as problem solvers and expecting them to participate in finding acceptable solutions for conflicts

- Communicating expectations clearly and praising children’s efforts to meet them

- Pointing out good decisions

When you see a child “fly off the handle,” know that the child decided to do so because it seemed the only option, whether or not the child is aware of having come to that conclusion after weighing alternatives. Brain research has revealed that when children experience prolonged or significant stress, a chemical reaction interferes with the “fight or flight” response, resulting in reactive aggression as a protective measure against a perceived threat (Bruno, 2011; Gartrell, 2011). Therefore children experiencing high levels of stress at home or in school may act out for reasons much more complex than a simple mischievous desire to break a rule or get something they want.

Automatically punishing reactive aggression only serves to make the situation worse, as punishment compounds the stress that caused the behavior in the first place. Sometimes it can be difficult to figure out what is going on when a situation erupts or a child consistently misbehaves, but it is important to do so in order to help the child make connections between feelings and actions so that he or she can begin to make better decisions.

© Hemera / Thinkstock

Children typically engage in frequent conflicts; developing self-regulation focuses on acquiring the ability to control impulses.

The Development of Self-Regulation

Self-regulation begins in infancy, as babies gradually learn that their needs will be met by responsive adults (Papalia & Feldman, 2011). For example, the newborn cries in response to all stressors (being wet or soiled, hungry, thirsty, and so on). Over time, baby learns to wait before crying as he begins to trust that when hungry, he will soon be fed, when wet, he will be changed, and so forth. Caregivers help infants and toddlers with self-regulation by providing a context and routines that are predictable and anticipating their needs when possible so they don’t have to handle too many challenges at once. When an adult remains calm while the child is angry or crying and uses words to describe what the child might be feeling, the child learns that his feelings are acceptable.

By interacting with babies and toddlers in routines—such as diapering, bathing, and feeding—and communicating what they can do to participate, adults help them to establish self-efficacy. For instance, while changing a 6-month old, the caregiver may say, “Can you lift up your bottom to help me get the dirty diaper out so we can put the new one on?”

More From the Field

Program director Lucia Garay explains the importance of self-regulation to emotional health.

Critical Thinking Question

- Lucia described teachers’ need to provide opportunities for children to control their own behavior. What implications does this have for the approach you might take to advance children’s self-regulation?

Some infant-toddler curricula include the use of signing with preverbal infants and toddlers to begin giving them tools with which to communicate what they need or want as well as “announcing” what they might choose to do (Vallotton, 2008). For example, a 12-month-old might learn to shake his head, signifying “no,” as he approaches a hot stove, to indicate that he has learned not to touch it. Similarly, he might learn to stroke his forearm to indicate that he knows he needs to use a gentle touch.

As children acquire language and become increasingly able to control their movements, early educators help preschool and primary children develop self-control by emphasizing that how they feel or what they think is not the same thing as what they choose to do. Thus adults need to first help them acknowledge or identify emotions and, second, learn how to express themselves and solve problems with words or other appropriate actions.

Acknowledging and Expressing Feelings

Suppressing or denying emotions teaches children that certain feelings are not permitted, or bad, and damages the self-esteem a child needs to make difficult decisions with confidence. Children are also sometimes frightened by the intensity of their feelings. Therefore three of the most helpful skills you can develop as a teacher are close observation, active listening, and modeling how to express feelings with words.

Close Observation

Close observation, or monitoring how children seem to be feeling and looking for signs of distress, gives you the opportunity to invite a child to open up and talk before losing control. Especially with infants and toddlers but also with older children, you focus on interpreting their body language, as sometimes children don’t know an appropriate word or the ones they do know seem inadequate to convey their feelings. As you get to know the children, you begin to recognize signals and can guess at describing how they are feeling.

Particular emotions have recognizable features, such as a red face or clenched fists (anger), diverted eyes or a crumpled body (guilt), or tears (sadness) (Bruno, 2011). Picking up on these cues, you might say to a child, “Your body seems all stiff and tight; I’m wondering if you are feeling mad about something.”

Active Listening

© iStockphoto / Thinkstock

One of the most important skills teachers need to acquire is the ability to “read” children’s body language.

Active listening means giving a child your undivided attention and accepting what is said without judgment. You reserve your approval or disapproval and focus on how the child chooses to act on his or her feelings. Active listening conveys and models empathy—that you care about how children feel and acknowledge that their problems are real and important (Hendrick & Weissman, 2007). Further, if you paraphrase, or repeat back in your own words what you heard a child say, you help teach the subtle difference between lashing out with words (to hurt another in an attempt to make oneself feel better) and the more constructive process of reporting to another person how you feel as the first step in solving a problem.

For example, LaToya, a 4-year-old playing in the housekeeping center, is pretending to make pancakes and goes to the refrigerator where play food is stored to get some milk. Mario is already there and takes out the very item LaToya wants. She turns to Mario, stomps her foot, and says, “No, no, stupid, that’s mine!” and then proceeds to try to take the milk away from him. The teacher steps in, saying, “LaToya, your words tell me that you are upset because Mario has something you wanted to use“ (paraphrasing). The teacher might follow with, “but you hurt his feelings with the words you used; can you try again to tell him what you need and see if he can help you with that?”

Modeling Talking about Feelings

Teachers can model how to talk about feelings as a natural part of conversation and to let children know that experiencing a range of feelings is normal. For instance, you might describe how pleased you are that you will be going out to dinner with friends for your birthday, that you are sad at having to say goodbye to your son going off to college, or that you felt frustrated because you were in a hurry but had to wait in a long line at the grocery store.

Finally, you can provide children with alternatives for expressing their feelings with words or actions that are harmless, such as:

- Using expressive materials like easel or fingerpaint, modeling dough, or clay

- Physical activities that release tension, like jumping up and down, throwing a ball at a target, or hammering pegs into a block of clay or a pounding board

- Redirecting to a soothing activity like swinging, rocking, or putting on a set of headphones and listening to music

- Using the “silent scream”—mimicking screaming as loud as possible without letting any noise come out!

Problem Solving and Conflict Resolution

© iStockphoto / Thinkstock

Teachers help children learn how to solve problems by modeling and coaching them through the necessary steps in a calm and reasoned process.

As children begin to identify, acknowledge, and express their feelings, they also need practice to learn how to solve problems and resolve conflicts. Key to this process is not only actively facilitating problem resolution when conflicts are happening but also having intentional conversations with children about decision making when they are not.

First, discussion provides an opportunity to think objectively and dispassionately about the kinds of problems children have or might experience. Second, children develop a shared sense of responsibility and ownership over the process. Third, identifying typical problems and brainstorming solutions provide them with resources—a “toolbox” of strategies they can draw from to try to solve problems themselves. Teachers need to keep in mind that there can be more than one appropriate response for a given situation and that children sometimes generate potential solutions that the teacher might not think of.

A teacher might encourage children to generate a list of scenarios and possibly useful strategies or solutions, writing them down on a chart posted in the classroom for future reference. For instance, to resolve conflicts over toys or other objects, the list of alternatives might include trading one object for another, asking to use the item when the child is finished, or asking to join the play and share. Later, when children are faced with a dilemma or conflict, those ideas can provide a place to start in solving the problem.

As with expressing feelings, adults can also help children learn to recognize good decisions by using instructive language that describes the choices they make; for example, saying, “I know you wanted the green marker very badly, but you made a good choice to ask your friend if you could use it when she was finished instead of taking it away from her.” Descriptive language helps children separate feelings from actions and understand that decisions have natural consequences that can be either positive or negative: “When you took the ball away from your friend, you made a bad choice because now your friend is upset and doesn’t want to play with you anymore; was there a better decision you could have made?”

In general, classrooms or care settings with a positive social/emotional climate have fewer confrontations, but young children do often have conflicts (Singer & DeHaan, 2007). Such conflicts typically focus on arguments about objects, physical encounters, entry to play, and ideas. There is wide consensus among constructivist theorists that conflict is a normal part of life which helps children learn about social and moral rules (Singer & DeHaan, 2007; Edwards, Gandini, & Forman, 1998). Teaching them to resolve conflict peacefully requires all of the above approaches—modeling, coaching, and direct teaching.

Some teachers use a process modeled after the Peace Table, a strategy first proposed by three-time Nobel Peace Prize winner Thomas Gordon (Teaching Tolerance Project, 2008). This process can be effectively used with young children because it gives them a concrete means for resolving conflicts. The principle behind the Peace Table is scaffolding—intentional assistance and modeling of a series of steps that the children gradually take over for themselves until they are able to solve a conflict unassisted and without prompting from an adult.

A place in the classroom is designated specifically for problem solving, with a place for two or more children to sit and a tool they can manipulate, such as a clock-face type of circle with movable hands to mark their progress through the series of steps listed below.

- Identify the problem.

- Teacher or child initiates mediation by inviting children to the Peace Table.

- Each child describes the problem.

- Teacher summarizes each child’s perspective using simple, clear language.

- As a group, children generate possible solutions. Teacher may offer prompts, but children’s ideas should be the focus of this step.

- Group agrees on a solution.

- Children offer one another a sign of friendship, such as a hug, to close the process.

- Teacher follows through by checking in with children to verify that the problem has been solved.

Table 9.4 documents how two children solved a problem using steps based on the Peace Table model.

Table 9.4 Sarah and Maria Solve a Problem

<span id=”w111418″ class=”werd”>

</span>

Rules vs. Guidelines

As early educators work to help children develop self-regulation, they need to identify socially acceptable behaviors as goals for them to achieve. Traditionally this has meant establishing a set of classroom rules for children to follow. However, research has shown that rules for young children tend not to be helpful because they:

- Are usually stated as negatives (e.g., don’t hit, no running, etc.), which can suggest to children that such behaviors are expected to occur (Wien, 2004)

- Tend to define the teacher’s role as one of technician/enforcer (Gartrell, 2012)

- Don’t provide information about what children should do (Gartrell, 2012; Readick & Chapman, 2000)

- Can result in labeling (e.g., good/bad children) and uneven application (i.e., being lenient with “good” children, stricter with “bad”) (Gartrell, 2012)

- Can lead to long-term problems with aggression (Gartrell, 2012)

While teachers need to set expectations for individual and group behavior, many experts recommend using a few broad guidelines—rather than many specific rules and punishments—so as to construct a positive classroom dynamic and climate (Gartrell, 2012). Guidelines for preschoolers and children in the primary grades should frame expectations in positive terms, such as, “We are careful with our bodies,” or “We use words to solve problems.” Guidelines should also be framed as open-ended statements to allow children to infer more specific friendly behaviors (like sharing a toy) from the general statement, “We are friendly with others.” They should be displayed or posted in the classroom or care setting with pictures and words as visible reminders of desired behavior. Caregivers who work with infants and toddlers (who are too young to verbalize guidelines) should use gentle prompts and modeling to help children meet expectations.

Positively worded guidelines function as standards—defining common goals that the community as well as individuals work together to achieve (Gartrell, 2012, p. 57). Finally, guidelines provide teachers and caregivers with opportunities to